This past weekend my husband and I flew to Scotland for a quick trip to see friends and family. It was the first time we’d been back in the country since moving to southeast England more than two and a half years ago. When I stepped off the plane in Edinburgh I was hit with the strongest feeling of ‘home’ I have ever felt. It makes no sense at all—I didn’t grow up in Edinburgh and have no family of my own there. I hate grey and rainy weather and don’t like being cold. But for some inexplicable reason Scotland got under my skin, and it’s there to stay.

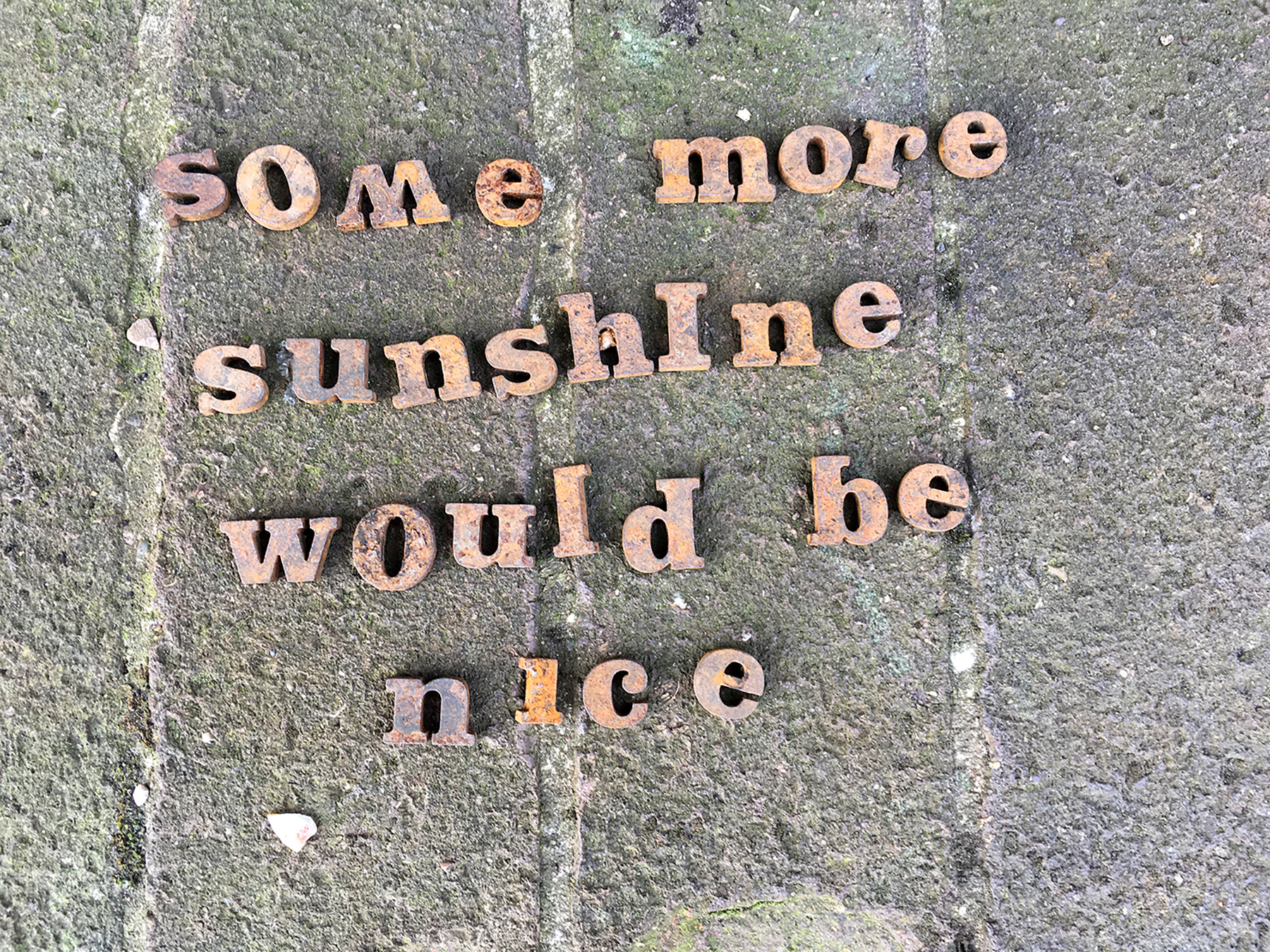

The only sun we saw on our entire trip was a peek under the clouds while the plane was landing. After a great night out with friends Friday, listening to live Scottish folk music in a small Edinburgh pub, we headed toward Perthshire in the waning afternoon light. We crossed the stunning new Queensferry Bridge, which we’d watched being built but hadn’t yet driven, beneath flashing road signs warning of heavy rains.

It was dark when we arrived at our country hotel, where we met my husband’s family for a party. Inside was perfection: cozy fires, good food, lovely folks, and a delightful selection of single malts behind the bar. Outside the rain came down and the air smelled sweet and nurturing.

The next morning, after a full Scottish with black pudding and tattie scones, we drove off through the Perthshire hills following empty winding roads along lochs and peat-black burns. A mizzle scrim hung in the air and the almost-solstice light had an underwater, half-lit feel.

We stopped in a few little towns we know, soaking in the Scottish friendliness of the people we met in shops and pubs. We couldn’t drink enough of the water, which tasted pure and nourishing and such a change from what comes out of the tap in southeast England. Back on the road we pulled over frequently, stumbling into bracken and moss-filled woods, remembering all the plants we first learned to call by Latin name.

The never-quite-light day felt like a dream. It ended Sunday night with a late flight back to England and an after-midnight crash into bed in Sussex. The next morning I wondered if it had even been real. Then I opened my refrigerator to souvenirs: a mountain of our favorite black pudding and a pile of tattie scones, ready to freeze for when we need a taste of home.